Have you always wanted to create your own NuGet package but not quite sure where to start? Let’s take a peek at how I built my Xamarin NuGet packages and how I distribute them using Azure DevOps!

Since my primary focus is Xamarin, the samples in this blog post will be somewhat Xamarin-minded. However, the concepts should also apply to other types of NuGets you are looking to create.

Creating the solution for your code

Building a plugin can be done in lots of different ways. The one I’ve recently settled on is James Montemagno’s Plugin Template which is a great starting point for rolling your own. It does, however, use multi-targeting which isn’t widely available on Visual Studio for Mac just yet. There’s a few preview builds out at the time of writing that support it, but it is coming soon! On Windows it is fully supported, however.

What exactly is multi-targeting? Essentially it means that you can make a .NET Standard 2.0 library and also target other frameworks such as iOS and Android from the same library. This reduces the number of projects and code you need to support all of these frameworks into one simple unified library. With multi-targeting, all assemblies are packaged inside a single NuGet package. People using your package can then reference the same package and NuGet will pick the appropriate implementation. Multi-targeting also allows you to use conditional compilation in your code.

Sounds great right? Enabling it is as simple as adjusting a few lines in the .csproj file of your .NET Standard library. Luckily this has already been set up in James’ plugin template I linked to earlier. If you’re not using that template you can adjust the TargetFramework line to TargetFrameworks followed by a list of supported platforms. These need to be separated by a semi-colon.

Your library will now get compiled for all of these platforms. Also notice the MSBuild.Sdk.Extras SDK being reference in the Project node. This is the SDK containing all of these additional platforms and should be referenced for this to work.

Writing some actual code

This is where you can let your creative juices flow. Write the code for your plugin for each of the platforms that you want to support. However, with all of that multi-targeting madness going on there is a specific method to structuring your code. If you’re developing for Xamarin you’re going to be creating code that will only work on Android or iOS, so how does the compiler know which bits should be compiled for which platform?

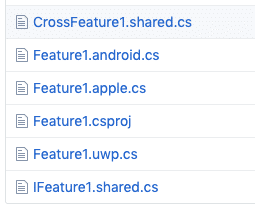

This is also defined in our .csproj file. By adding a few ItemGroup nodes to our project file we can separate files per platform based on a naming convention. In the sample below we suffix our files using the name of the platform they need to be compiled for. By sticking to this naming convention we ensure that everything ends up where it needs to go.

Files for multiple platforms in the same library.

Files for multiple platforms in the same library.

Preparing the NuGet package metadata

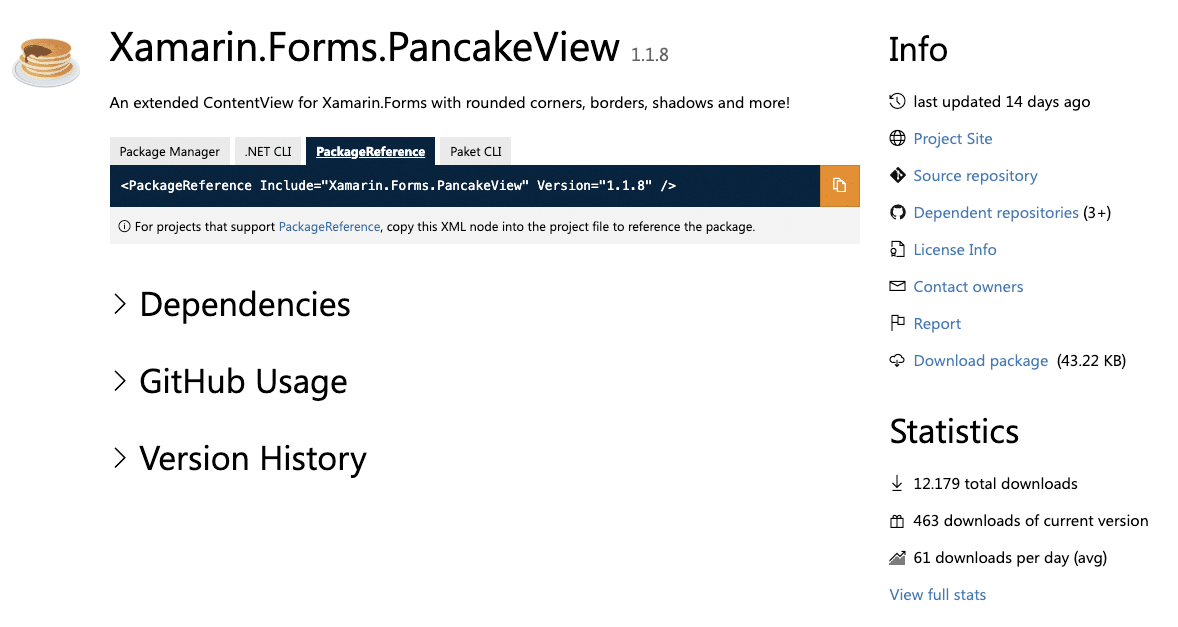

Each NuGet package out there has some metadata telling potential users what it does and where they can find out more information about it. Where does this information come from? If you’ve read the rest of this blog the answer is probably already obvious to you: the .csproj file.

Spice up that NuGet package page!

Spice up that NuGet package page!

Pretty much everything related to your NuGet package can be set from the project file. I will talk more about automating a few of these things such as version numbers later on in this post. Most of this stuff is something you set once and will hardly ever update.

There’s a few variables in there that will be replaced when building. These are in parenthesis and prefixed by a dollar sign. You can leave these in and the build will automatically fix them for you.

Setting up a CI build pipeline

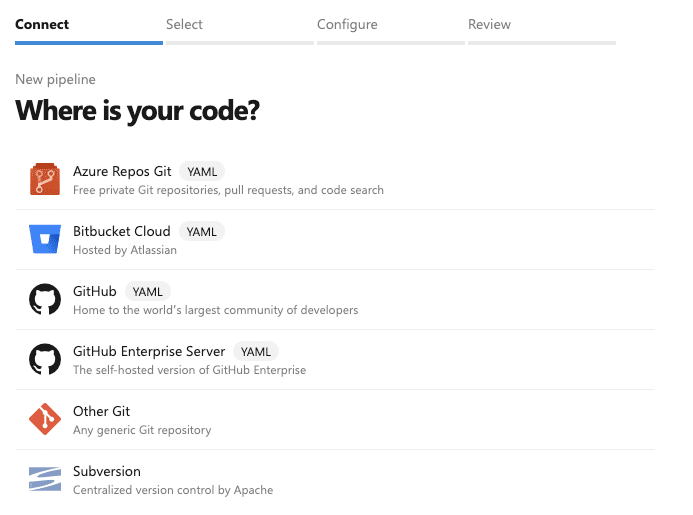

There are numerous ways of getting your package onto the NuGet feed. I like automating these steps and what better tool to use for that than Azure DevOps? Even if your NuGet code resides in an external system like GitHub you can still hook up a pipeline for both continues integration and deployment. On top of that, it’s free for public repos!

Creation of a new build pipeline.

Creation of a new build pipeline.

Let’s start by creating a new project on Azure DevOps and navigating to Pipelines > Build. Hit the button to create a new one and you should be presented with the New Fancy Pipeline Creation Experience (it probably has an official name). This process uses a language called YAML to define your build pipeline. First, we need to choose where our code resides, I chose GitHub for this sample. You might run into an authorization request from Azure DevOps to access your repository. Grant it access and you should be able to proceed.

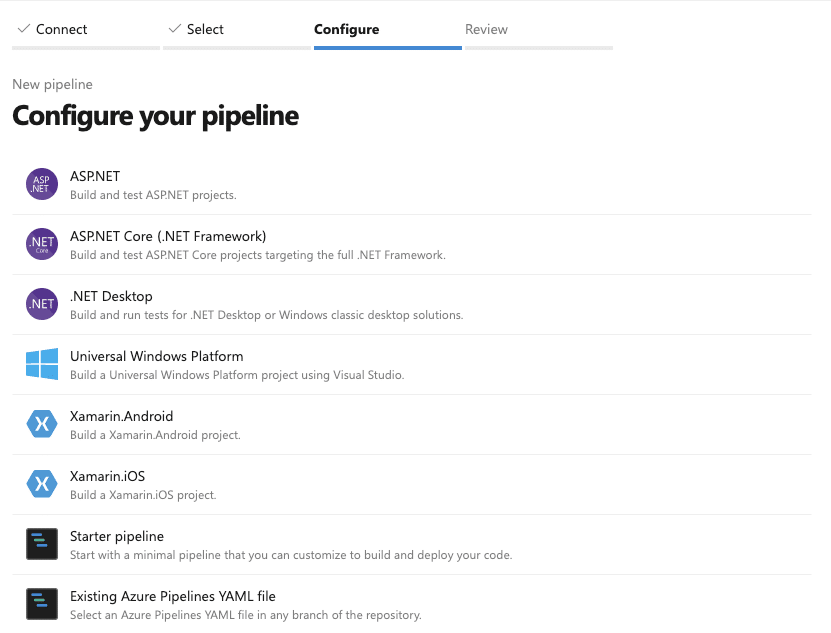

Choose the type of pipeline you want to create.

Choose the type of pipeline you want to create.

Let’s write some YAML

Next up we will need to choose the type of pipeline to create. I went with the Starter pipeline which brings us to the YAML editor. YAML is the new standard for defining build pipelines from code. I personally prefer what is now called the Classic Editor, but apparently the majority of people these days likes to type moarr code. To save you from doing that, for now, you can copy the following code and make a minor adjustment to point to the .NET Standard .csproj file we created earlier.

After copying this in you can hit Save & run to verify that the build runs successfully. When we do that we also run into the reason people love the new YAML-based pipelines; they easily can be stored in your repo making them re-usable and version-controlled! I’ve added some comments in the YAML definition to clarify what all the little bits mean.

Setting up the release build pipeline

After taking care of continuous integration to make sure the build doesn’t get broken by PRs we need to create a pipeline that actually creates releasable artifacts. We can do that by creating another build pipeline using the YAML file below. This is a more extensive one, so be sure to check the comments in there to see what all the steps mean.

In this build pipeline, we build the project using additional MSBuild arguments to pack both a beta and a release version of the NuGet package. The build number which becomes the package version comes from the build pipeline and simply increments itself on every build. After we hit Save & run on this pipeline we should get two artifacts.

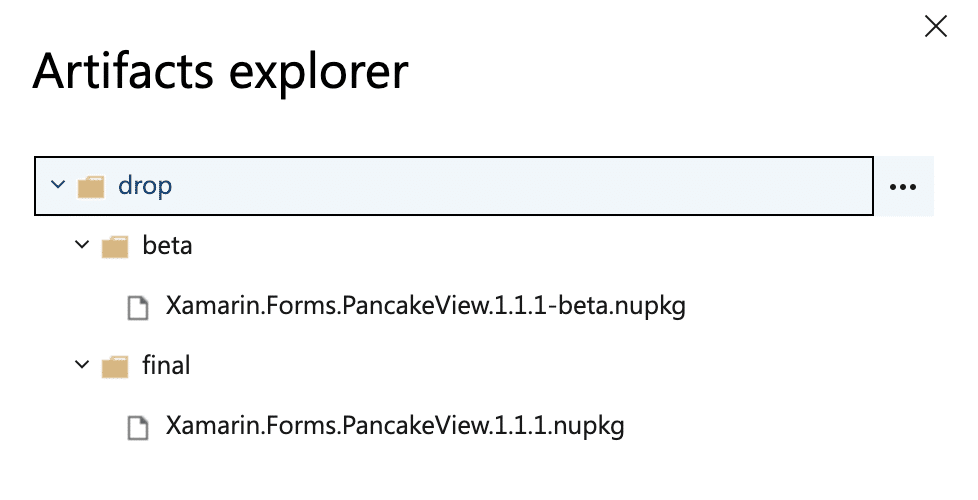

The build artifacts for our release build.

The build artifacts for our release build.

Why do we want to build two artifacts at the same time? It keeps the version numbers the same, meaning we can be sure that the same version of the plugin is available in both beta and when we push it towards a final state. That way our NuGet package’s version history remains clean and manageable.

Setting up the release pipeline

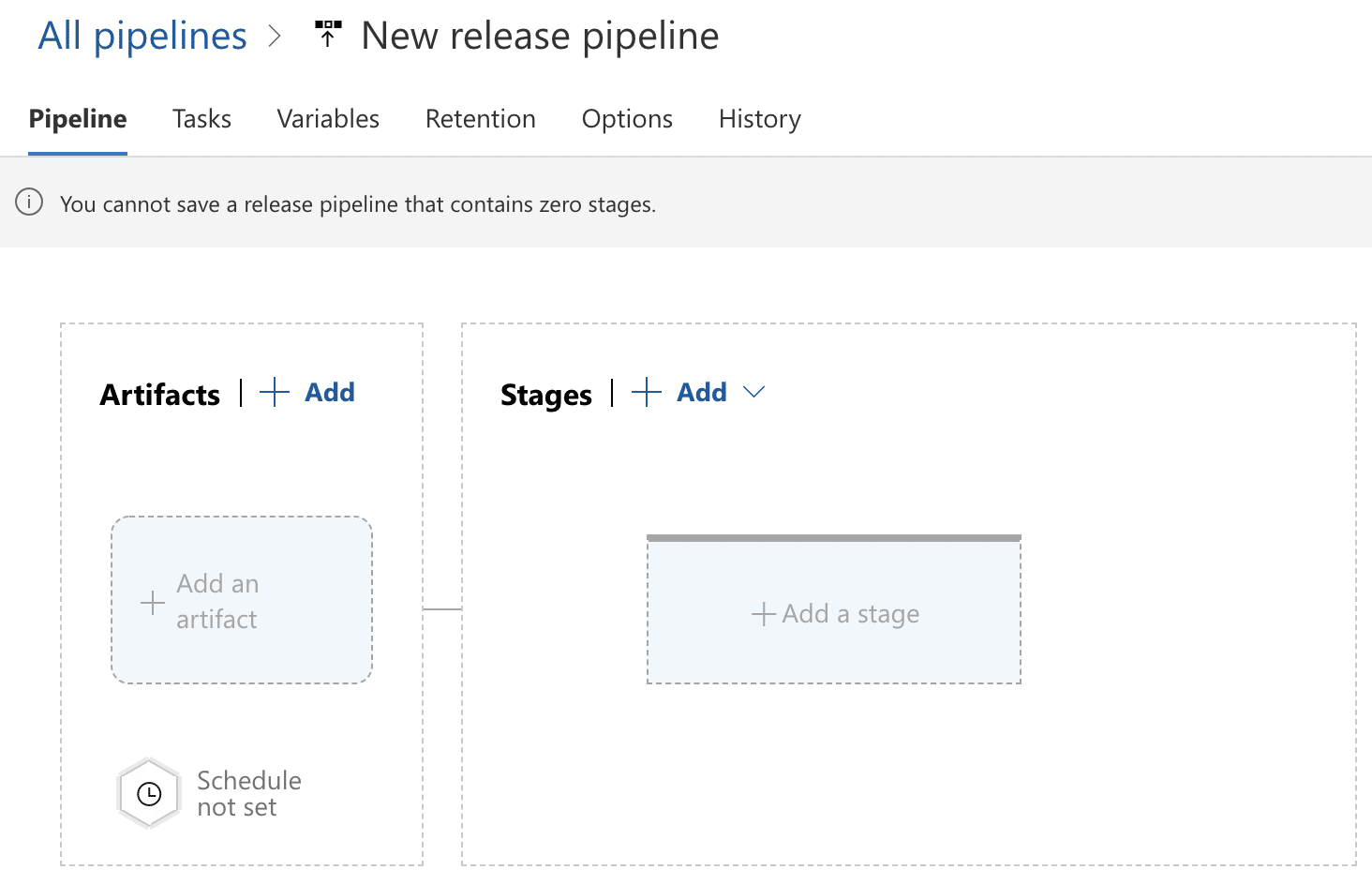

The release pipeline is what publishes the .nupkg files we created in previous steps to the NuGet feed. At the time of this writing, it is built using a similar editor to the Classic Editor for build pipelines. There is no support for creating release pipelines through YAML (yet). Start by creating a new release pipeline and you should end up with a screen similar to the following.

A new release pipeline, fresh out of the box.

A new release pipeline, fresh out of the box.

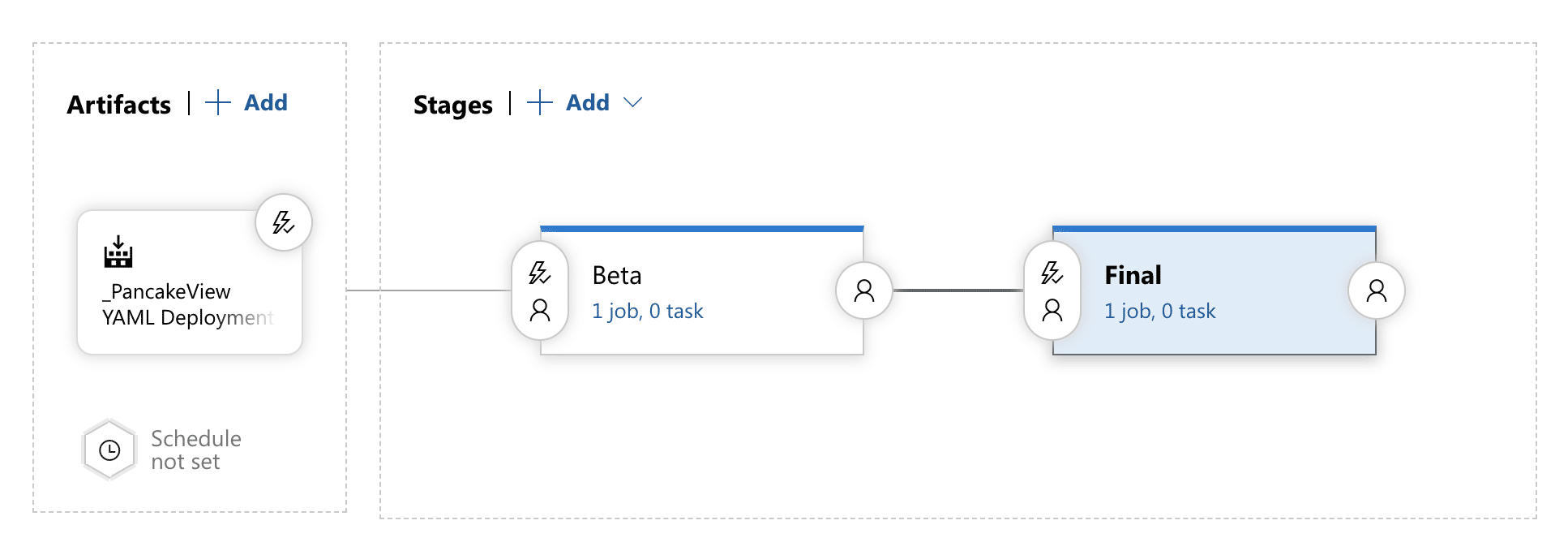

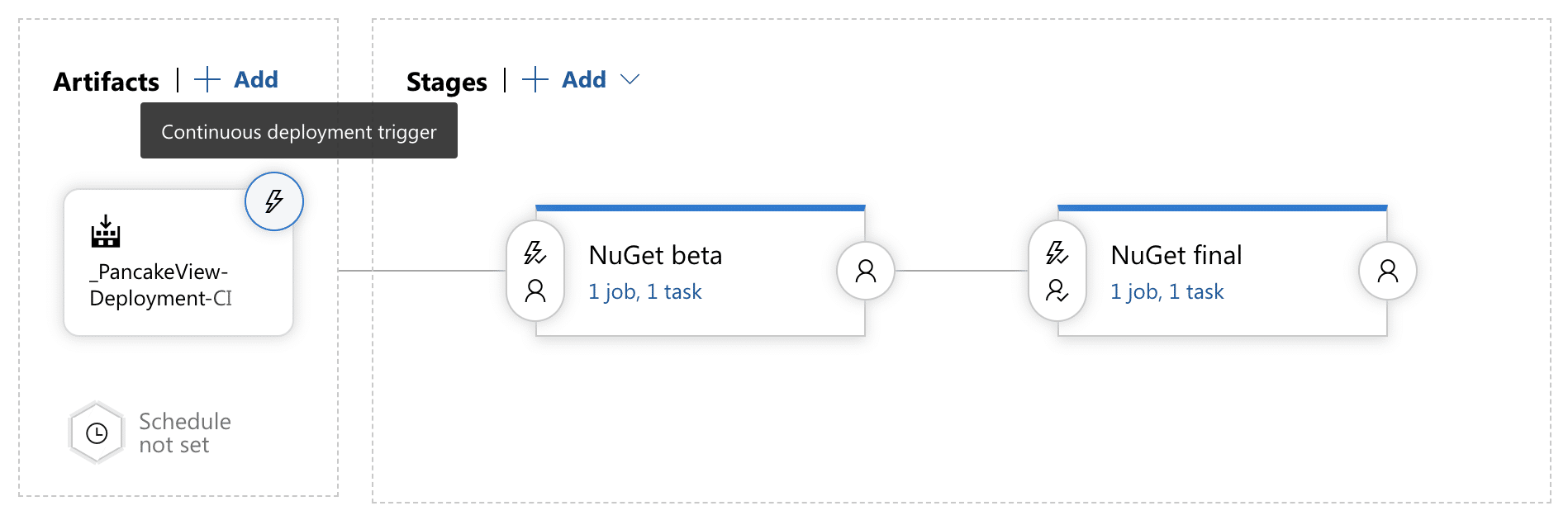

On the left-hand side of the screen, we can pick the artifacts that will serve as the input of this release pipeline. In our case, that’s the result of the release build we created earlier. Click to add the artifact, select the correct build pipeline and click Add. Next, add 2 stages and name them Beta and Final. Choose the Empty Job template for these stages. You should end up with something looking like this:

Building the release pipeline step-by-step.

Building the release pipeline step-by-step.

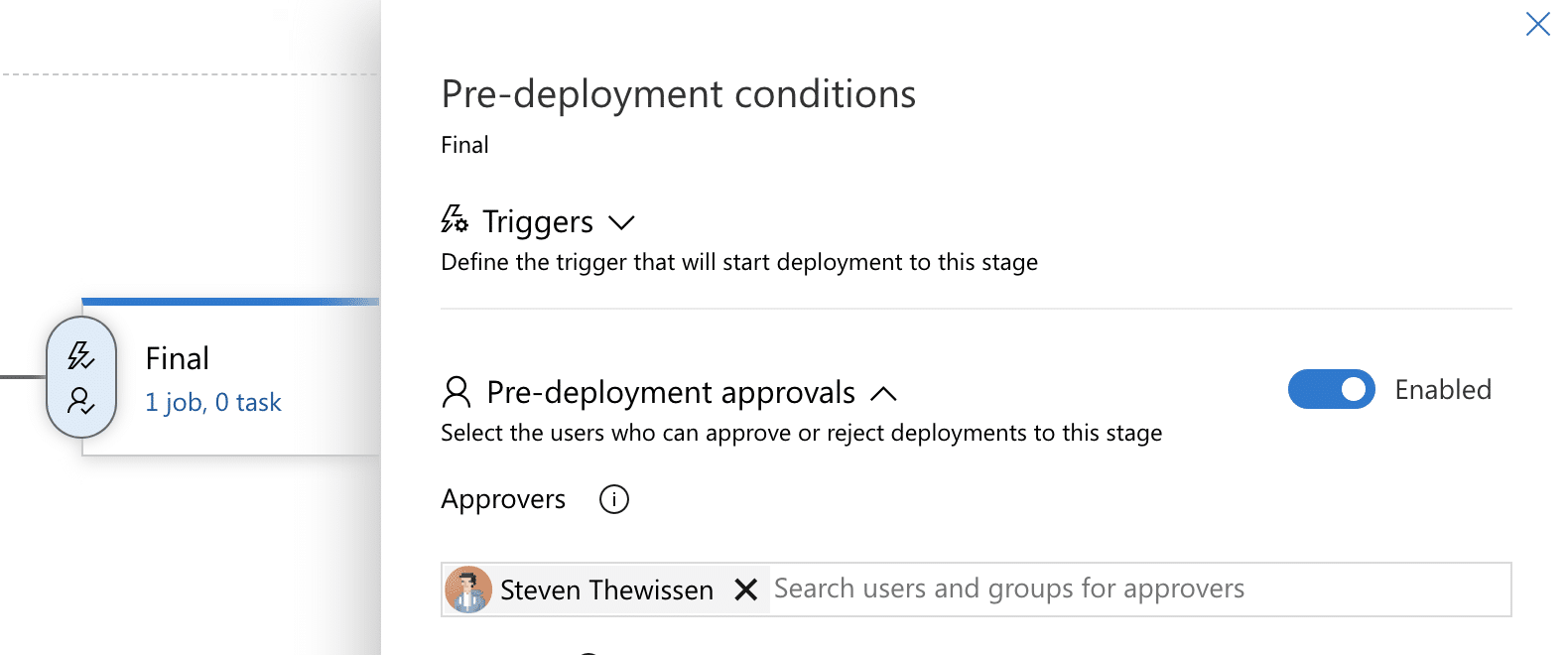

Adding an approval gate

Before we can start adding the tasks into each of these stages we first want to make sure that there’s a gate in between the beta and final stage. Obviously, not all of the builds that end up in the beta stage will get released. We add this gate by clicking on the Lightning/Person icon next to the Final stage. Enable Pre-deployment approvals and add yourself or whoever else will be the one to push a release to production.

Not every beta build will go to production.

Not every beta build will go to production.

Adding the NuGet publishing tasks

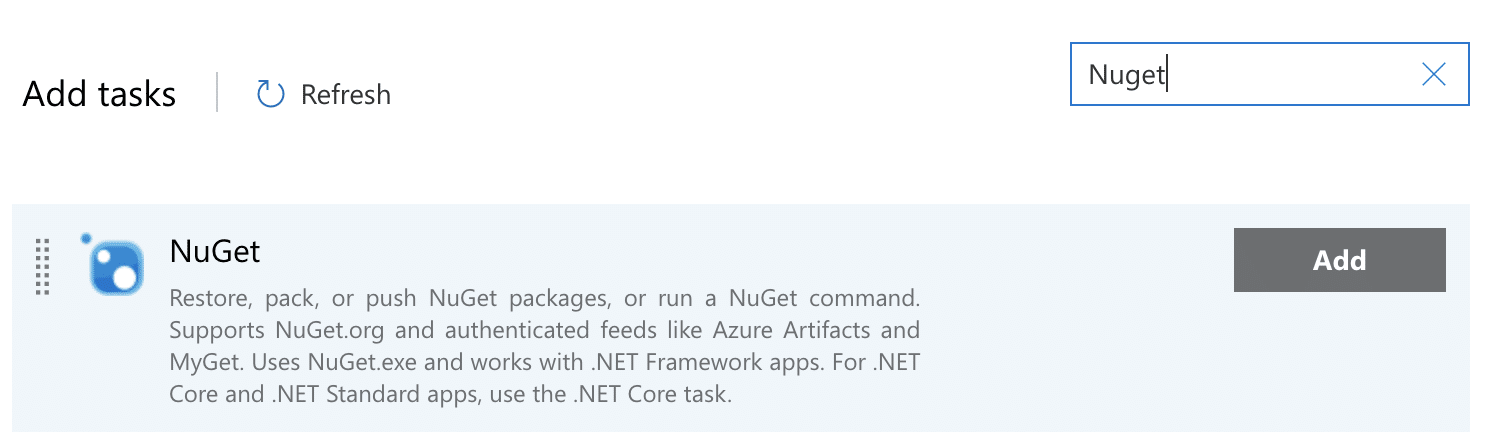

By clicking on the Tasks tab at the top we can add a task to both stages of the deployment. Add a NuGet task to each of the two stages and set its command to push.

The NuGet task to be added to each stage.

The NuGet task to be added to each stage.

We also need to set the Path to NuGet package(s) to publish but this one is different for each stage. Add the following values for each stage respectively:

- Beta:

$(System.DefaultWorkingDirectory)/**/drop/beta/*.nupkg - Final:

$(System.DefaultWorkingDirectory)/**/drop/final/*.nupkg

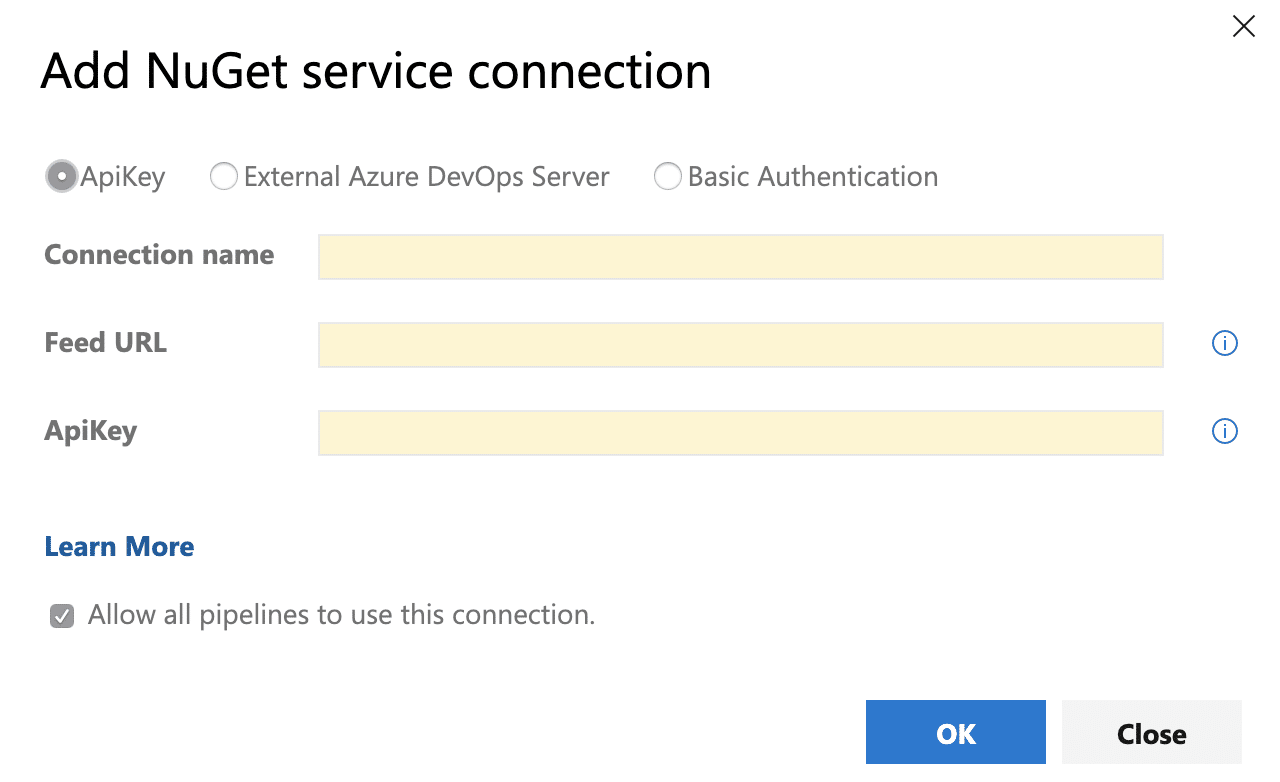

Set the Target feed location to External NuGet Server because we will be using the normal NuGet feed and not one hosted on Azure DevOps. The last thing left to do now is setting up a service connection to NuGet.org. This service connection is what Azure DevOps uses to publish your package and link it to your user account. Hit the New button to start setting it up.

Create a service connection to NuGet.org.

Create a service connection to NuGet.org.

Setting up the service connection to NuGet

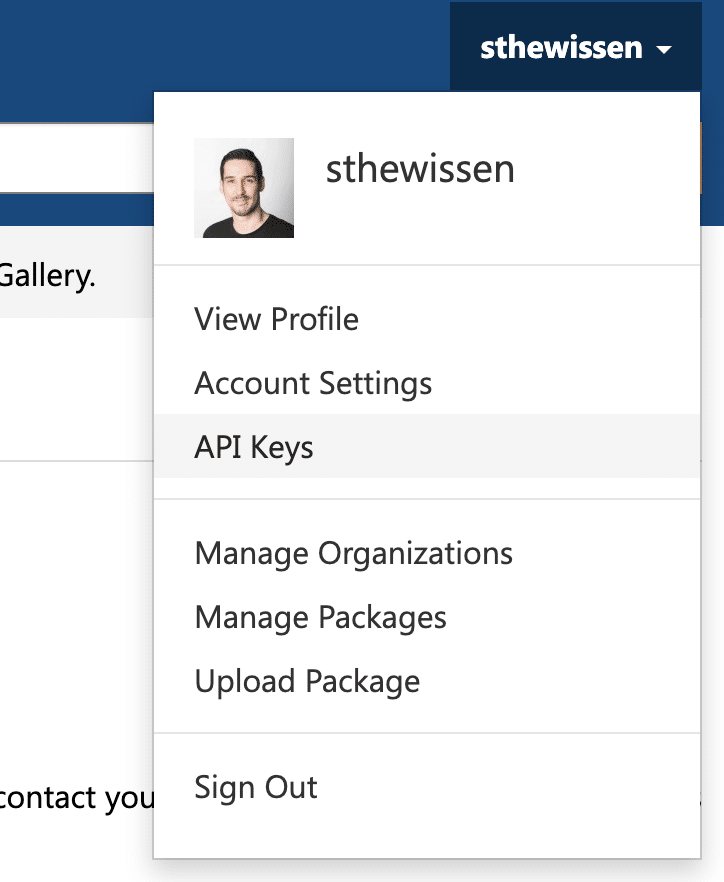

To get our service connection up and running we need to set up an API Key on NuGet.org. Let’s start by going there and logging in to a valid Microsoft account. This will be the account that is used to link these packages to and identify them as your own. Click on your username in the top-right corner of the screen and choose API Keys to create an API key to use in the service connection.

Add an API Key on NuGet.org.

Add an API Key on NuGet.org.

We can now complete the service connection dialog:

- Connection Name: [Your choice]

- Feed Url: https://api.nuget.org/v3/index.json

- API Key: [Key you just generated]

Hit OK to finish the creation of the service connection and hook it up to the NuGet push task in each stage of in our release pipeline. Save the release pipeline and we should be good to go! However, there’s one more thing we need to decide…

To continuously release or not?

This release as it sits now is something that we need to manually trigger. That might be just fine for you, however, it’s also possible to make it trigger automatically once a new successful release build has become available. To set this up we simply need to click on the lightning icon next to our artifacts and enable Continuous deployment, simple as that!

Making our release pipeline run on each successful build.

Making our release pipeline run on each successful build.

The final steps

There’s not a lot left to do now. Simply run the release build and all of the pipelines should take care of the rest. You can proceed to log in to NuGet.org to view all of your packages and list/unlist them. You can also view your package statistics from here. Whenever a new version is published you will receive an e-mail as soon as it’s become available.

That’s pretty much it. If you have any questions, remarks or have found anything in here to be incorrect, please let me know! You can find me on Twitter which is where you can probably reach me the quickest. Thanks for reading.